-

Introduction

In January 2020 I was invited and gave a presentation at the symposium to mark the coming to a close of Professor Tineke Abma’s substantive post at the Vrije University, Amsterdam. Being invited to talk about participatory research, specifically its meaning and messiness, was both an honour and a pleasure. This article evolved from that talk.

-

Background

Over recent decades, in social policy, social care and health research there have been moves to elevate the value of public involvement and participation in research that engages with the complexities of social situations. There has also been recognition of the value of informal knowledge and knowledge exchange systems present in communities. In reality, however, the world of policy research for social and organisational change continues to be driven by ‘knowledge economies and managerial demands in which certain types of knowledge and productivity rank above others as sources of evidence and value (e.g., metrics, evidence-based medicine)’ (Filipe et al., 2017: 2). Such research generally follows a tight, prescribed method that produces evidence of whether a particular hypothesis is realised as an outcome at the end of a research process. Standardised methods that produce outcomes at the end of the research process have the weight of convention behind them. They are almost culturally embedded as the most reliable methods. The search for a simple truth that captures externally devised objective measures for worthwhileness can, however, leave the research site whole, its fabric undisturbed and the basis for further development unknown. They are, therefore, less likely to produce a sound foundation for programme development than one that disturbs external notions of quality and captures the essence of community complexity (Cook, 2006).

Participatory research approaches frame research as an emergent and complex collaborative endeavour. A range of voices prods, questions and critiques not only what is being researched, but the way in which it is being researched. Learning together as a means for taking action is a key element of the process. This involves creating supportive, relational spaces for finding out what can be known, for creating knowledge that was not even envisaged at the beginning of the research. Participatory research (PR) brings together assumptions and knowledges drawn from a range of people involved in the research. It then creates spaces for those people to subject their own knowledge to personal and collective questioning and critique as a springboard for learning about what ‘could be’ rather than ‘what is’. This social learning system demands complex relationships for co-constructed practices. It is likely to be a messy process, particularly if the knowledge of others, including the knowledge of the seldom heard, destabilises the very assumptions that underpin accepted pathways and processes for acting. It is also a generative process leading to different and sometimes unexpected ways of understanding forms of knowledge and associated actions that could not have been known at the outset. The processes of PR can therefore be ambiguous rather than defined. This is challenging for those who fund or commission research to improve social circumstances but who conceptualise research as a linear, outcome driven approach or a process of affirmation that will, at best, reveal gaps in an otherwise undisturbed system.

In the UK, PR has been seen as a logical extension of patient and public involvement (PPI). PPI incorporated the voice and expertise of those with lived experience and/or the public into health and social care research. In 1996, the National Institute for Health Research instigated INVOLVE, an agency that supported active public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research. PPI comes from a research paradigm where research is generally designed and led by external experts who seek to incorporate, through involvement, a wider range of voices. The key feature of PR is, however, that participation is the starting point, its central tenet rather than the incorporation of voices into predetermined approach. In PR the active agency of whose life or work is the subject of the research can be seen in all stages of the research process. Starting from building relational spaces with those involved the intention is to co-construct the research process. What can be known from that process, the new knowledge and subsequent actions, evolves through shared endeavour. While all PR might be described as PPI, the same cannot be said in reverse. PR is fundamentally located in a dynamic form of participation that is central to its function and values. In the call for more participatory research, this very different way of creating research spaces is less evident in the commissioning of research. Whilst policy is participatory, the defined parameters for gaining funding remain framed by notions of predetermined methods, linear processes and clearly defined outcomes: indicators of rigour, validity and accountability drawn from another paradigm. The trustworthiness of building ‘relational spaces’ and creating ‘mess’ is more often seen as bias and poor planning, elements to be avoided rather than celebrated (Cook, 2012). Trying to fit a ‘round peg into a square hole’, fitting one research paradigm into the rules of another, suggest that the fundamental principles of PR, and understandings of its potential, had yet to be truly appreciated.

-

What does it mean to do participatory research?

Although the term participatory was used more widely in the late 1990s (McTaggart, 1997), it was neither a term nor a practice widely in use in the UK, particularly in health research, where more bounded forms of research, such as experimental randomised controlled trials, were prevalent. Where it was used, ‘participatory’ tended to mean that research directly involved people (such as qualitative forms of research), that people with lived experience were on advisory or steering committees or that methods had been incorporated that engaged participants in data collection. These approaches were often hailed as participatory research. Whilst engaging with people with lived experience holds the potential to have an impact on research outcomes, it is likely to have a very different look, feel and set of impacts compared with research where ‘the participation of those whose life or work is the subject of the research in all stages of the research process’ is the hallmark of the research approach (ICPHR, 2013: 6). The notion of doing research in a participatory manner was being interpreted so broadly that it became dogged by what Edelman (1964) termed ‘illusory consensus’, i.e. those that use a word (particularly common words such as participatory, inclusion, partnership) think others will attribute the same meaning to it as they do themselves. It is possible, therefore, for each person to have a somewhat different understanding of that word and to act on it differently. It is important to know what ‘to do’ PR means, what set of principles and values drive the practice of this form of research and what we might expect it to achieve. As PR is an evolving process where new learning contributes to practice, rather than a set of methods to be slavishly followed, the meaning cannot be fixed by set definitions, instead it has to reflect the unpredictability of engaging in complexity and ways of determining value that move beyond the observable and the measurable.

Communicative spaces: In PR the primary underlying assumption is that collaborative participation on the part of those whose lives or work is the subject of the study fundamentally affects all aspects of the research. In PR, participation should run through it as letters through a stick of Blackpool rock.

Figure 1. Letters through a stick of Blackpool Rock

What is valued in PR is not only what is already known, but how that which is already known can be developed to make socially just changes. These changes are based on knowledge generated from the participatory endeavours of communities of practice. Communities of practice are social learning systems that engage in activities, conversations and reflections. They produce physical and conceptual artefacts such as words, tools, concepts, methods, stories and documents that reflect the shared experience (Wenger, no date). These communicative spaces for learning draw on Habermas’ notion places for ‘… mutual recognition, reciprocal perspective taking, a shared willingness to consider one’s own conditions through the eyes of the stranger, and to learn from one another’ (2003: 291). The value of each person’s contribution can be seen in the co-creation of the research process, the generation of data, and the approach to making meaning of the data we generate (analysis). How we understand what is important for communities of practice and wider society, the actions, changes (impact) that arise from the research process, and what messages are disseminated beyond the research, is based on these principle of participation.

Accepting uncertainty: When research is initiated there is likely to be an overarching aim, especially if the research is to meet a funding call. The finer detail of that aim (iewhat then becomes the critical research question that drives the research endeavour), will then be generated from shared discussion amongst those who live and/or work might be affected by the research. This is alongside, but not driven by, any external facilitators for that research process.

Accepting that questions and hypotheses may be amended as knowledge is developed through the processes of the research, that even the co-constructed process is not fixed, means accepting some uncertainty, that expectation will be disturbed and that learning will be integral to, rather than a summative outcome of, the research process.Relationship building: The bedrock for open communication and acceptance of uncertainty is the building of relationships to form mutual respect. In PR the process of building a collaborative learning environment, outlined by Reason (1998) as being the space where people are ‘both invited to engage in work which is important and meaningful for them, and also insist that they reflect on the manner in which they perform that task so that together they learn how to move toward a more genuine collaboration’ (p. 153), necessitates the building of trust and respect. The way this occurs will vary across projects, depending on starting points. It will take time to learn about and create possibilities for ‘authentic participation’, where participants share ‘in the way research is conceptualised, practised, and brought to bear on the life-world’ (McTaggart, 1997: 28). Building relationships involves valuing what is known and valuing the perspective and knowledge held by all members of the group. If those whose knowledge is generally excluded from decision making have this reinforced, if their voices are not heard and incorporated into thinking, they remain outside the group, wary of those who are exerting their form of knowledge. This has implications for building trusting relationships that allow for open communications.

Collective self-reflection as critical enquiry: Having opportunities to understand and celebrate what is known before going on to find ways to hear beyond dominant knowledge and ways of constructing knowledge and learning is demanding of both time and care. It is, however, at the heart of PR. Communication is not just about hearing what others say and then arguing for your particular conceptualisation of a situation with the aim of winning others over to your understanding of it. It entails a more complex engagement that challenges members of a group to conduct what Kemmis and McTaggart (1990: 5) termed ‘collective self-reflective enquiry undertaken in social situations’. This starts from articulating personal thoughts. Attempting to articulate aloud thoughts that have been swirling around in our heads but that we have not, as yet, made sense of (tacit knowledge; Eraut, 2000) forces these thoughts to surface in a way that is recognisable to others and so to oneself. ‘What is articulated strengthens itself and what is not articulated tends towards non-being’ (Czeslaw Milosz, quoted in Heaney, 1999).

In PR, engaging in this discursive process is not only about seeking out similarities, although this is a good start. It is also about seeking out differences and understanding those differences. In this space the different cultural underpinnings for knowing that exist when, for instance, professionals/practitioners, who have studied the theory and practice of a field come together with those who are experiencing the actuality in an immediate and dramatic way, are brought together. This process underpins the growth of both personal and collective knowledge. It is not concerned with whose knowledge is most important but rather what we collectively construct from our shared knowledge that supports more radical change. The aim is to ‘transcend the “your/my culture” dichotomy to creatively find ways to incorporate both [cultures]’ (Lenette et al., 2019). The process necessitates becoming critical, where critical means enquiring and is not seen as a negative. This necessitates letting go of long-held beliefs, assumptions and certain ways of thinking and acting. Doing this is not easy and requires mutual trust. Many people engaged in this describe beginning to let go of some of their ways of seeing as an outcome of engaging with new ideas. This leads to not knowing what they are doing and the feeling of being ‘in a mess’ (Cook, 2009).

-

The purpose of mess

Articulating thoughts, especially out loud to others, and being open to the thoughts of others creates opportunities for reflecting on those thoughts and prepares the ground for the dawning of the new. It can disturb both individual and communally held notions of knowledge that shape actions and disrupt well-rehearsed notions of practice. The old ways have been disrupted and new ways are unformed and unproven. This is likely to be destabilising and messy. Yet this mess has a purpose. It is in this messy area that ‘reframing takes place and new knowing, which has both theoretical and practical significance, arises: a messy turn takes place’ (Cook, 2009: 277). Striving to maintain personal certainties, to not get into ‘a bit of a mess’, restricts opportunities for learning. This is not just any kind of mess, however. Not the haphazard mess derived from the throwing of elements into a pot never to be surfaced and reflected upon, what we might see as general mess.

Figure 2. General mess

Nor is it the same mess, shown in Image 3 below, when all the elements are predetermined, just muddled, and merely needing to be sorted to produce the required picture.

Figure 3. Mess that produces a required picture

It is the type of mess that challenges you to create something new, where there is a range of known building blocks but what can be created from these is, as yet, unknown. It is both familiar and unfamiliar at the same time.

Figure 4. Mess with creative potential

As Reason (1998: 154) suggests, ‘the clarity of the present and the as-yet undefined possibilities of the future, [provide] a gap which stimulates the imaginative capacities of the participants’. It is the space for new ideas, the space where, as this man (from a former project) described, you can let your ‘mind slip’:

The more things just got blown into the air, the more fun it was …When we were discussing and debating stuff, during some of the discussion that we had, your mind slipped a few times before it settled. It’s like you started it off and someone would say something, and it would be like, ‘Erm, I’m not quite sure of…’ And then it started a bit of a debate up. And then by the time you finished the debate you had most of the answers and then it was like, ‘Erh…, you know, we’ve just answered it. (David: Cook & Inglis, 2008: 63)

The ‘messy place’ is unsettling, exciting and challenging. Disruptive of habit and custom it can provide the context for purposeful discovery based on shared, but mutually contested interpretations and understandings. It creates opportunities for learning and change that have been subjected to rigorous individual and collective critique fashioned from bringing together positions of similarity and difference. Giving voice and having agency in the decision-making process, including those whose voices are seldom heard, and even less likely to be acted upon, is a key principle of PR.

-

Challenges from (and to) the field

The notion that research starts with a hypothesis, a research question, a set of predetermined methods to be adhered to, and that it moves forward in straight, contained lines until outcomes occur at the end is a recognised framework for indicating the quality of certain forms of research. In clinical research, for instance, Yang, Chang and Chung (2012: 979) note that ‘Rigor results when strict conduct, accepted specialty standards, and rational interpretation are present … When a study fails to measure what it intends to measure, validity of the consequent result declines and evidence provided by the study is suspect.’ Suggesting mess might be a vital element for building rigour into research processes requires a shift in perception from the more usual foundations for research that posits the tidy, replicable and contained as a quality marker. PR further challenges more prevalent understandings of research rigour because its starting point, the basis for building confidence for constructive messes to occur, is relational partnerships. Mess through relational practices would appear to break a key rule of a dominant research paradigm that requires that bias should be addressed by researchers being distanced from their subjects. To ‘get into a warm bath’1x Colloquial term meaning no longer being able to be objective as those involved are too close to each other. with research participants (something of which I was accused when undertaking action research with families in the mid-1990s) is seen as adversely affecting the opportunities for collecting untainted data. The implication is that building relationships is detrimental to true critical enquiry, that as a researcher you could/would be drawn on to the side of those being researched and as such lose your criticality. Building relationships in PR is construed as a process for enabling greater criticality. Collaborative discussions, built on strong relationships, can create a rich set of understandings from a range of perspectives that go beyond those of the lens of an individual. When working collaboratively in this way there is no single steer that corrals understandings into the corner of the researcher, or the corner of those who are the most likely to be able to articulate a strong view. In order to enact constructive change, dialectical conversations among those involved in, and affected by, particular practices are undertaken as reflexive practice and recursive practice, i.e. what is known and acted upon is repeatedly subjected to new dialectical conversations in an iterative manner.

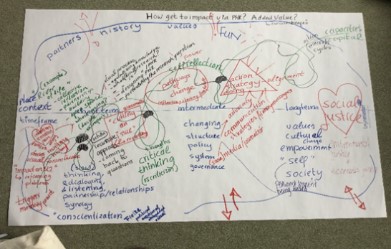

The photograph below (Image 5) shows a mapping process undertaken by members of the ICPHR in attempt to portray the trajectory of the participatory approach to health research. Produced in a workshop in Bielefeld, Germany (2015), the drawing presents ‘a complex web of non-linear, “messy” routes to impact connected to histories, values and activities and demonstrate the intermingled nature of PHR in action’ (ICPHR, 2020: 7).

Figure 5. Trajectories for participatory health research (ICPHR, 2020: 8)

This messy representation is very far from the more defined and linear research trajectory of experimental forms of research that seek to measure outcomes. This research approach holds a different set of assumptions about intended outcomes, ways of reaching those outcomes and how outcomes are demonstrated. The shapes of these research processes are overlapping and complex, as described by Wadsworth (1998: 5).

… while there is a conceptual difference between the ‘participation’ ‘action’ and ‘research’ elements, in its most developed state these differences begin to dissolve in practice. That is, there is not participation followed by research and then hopefully action. Instead there are countless tiny cycles of participatory reflection on action, learning about action and then new informed action which is in turn the subject of further reflection. Change does not happen at ‘the end’ – it happens throughout.

The more didactic, measured, linear processes of experimental research can be difficult to shake off, particularly for research in health where evidence-based medicine has become elevated as a quality marker and randomised controlled trials are seen as the gold standard. In my early years as a researcher, I found I was straining against what were probably self-imposed ‘oughts’, the things that should be done to create rigour and acceptable research practice. Working without a clear trajectory for the research, letting the research move whilst learning more about what underpinned issues and actions, following emerging rather than pre-formed theories and assumptions, ran counter to traditional training. Doing action research in this way was described by Mellor (2001) as our guilty secret. This approach to research, overtly aimed at using shared knowledge and learning to transform social situations, ‘… to overcome felt dissatisfactions, alienation, ideological distortion, and the injustices of oppression and domination’ (Kemmis, 2001: 92) had yet to gain wider traction.

-

The FaBPos Project

The aim of the FaBPos project was to research the basis for designing a successful course, using Mindfulness and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) with family carers in long-term caring roles of people with learning difficulties and challenging behaviours. The aim was not to produce a set package for a course that could be taken off the shelf and replicated by others, but to research what features might be essential for others to adopt in their own work. The study would contribute to the development of theories for and understandings of:

what family carers needed to help them stay resilient to the ongoing, long-term stresses of living with challenging behaviour;

appreciating that there were likely to be recruitment issues, what helped family carers recognise the need for such a course to support their resilience;

what elements of the course were successful in supporting the resilience of family carers?

I have worked with people with learning difficulties and their families since the early 1980s. Some of the children I met when they were 6 weeks old are now in their 30s; their parents are my age (early 60s or older) and are still caring for their son or daughter. This means family carers lead complex and stressful lives. Their caring role can leave them isolated and unsupported. Effective services designed to build resilience for people in long-term caring roles are lacking in the UK (Cook et al., 2019: Griffiths & Hastings, 2014).

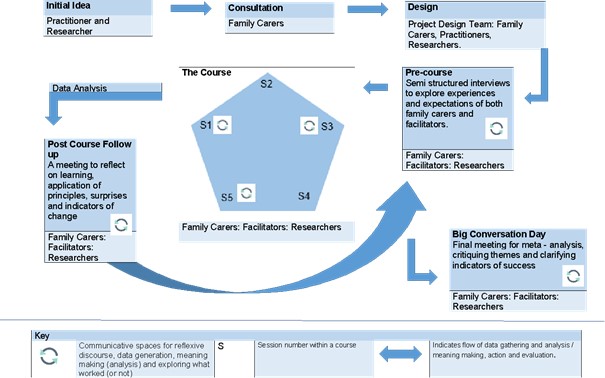

Prior to undertaking the main research project, the original project team (a consultant clinical psychologist with a wealth of experience using Mindfulness/ACT, myself (a university academic with experience as a practitioner working with family carers and of facilitating PHR) three family carers and a research assistant) sought funding to consult with family carers in the local region about their caring experiences and their support systems. (Funding for discussing research with those who might be involved prior to doing the research is not currently widely available: a key issue for those wishing to do PR.)

Discussions with four mothers, one sister, one grandmother and two couples (mother and father) were held in their own homes and four group discussions were held in family carer centres with 12-25 family carers per group. Informal conversations were also held between family carer members of the project team and family carers they knew. In addition a group of family carers volunteered to attend a trial run of an adapted Mindfulness/ACT workshop similar to the one being proposed and to comment on the way in which it was organised, and how it might be made more available for family carers. What was learned during all the consultations was brought together and contributed to the design of the research. This included adapting the proposed time of day and length of the course, where it was held, how it was described to family carers and where it was advertised. The final design focused on three separate courses, each consisting of 5 x 2-hour weekly workshops on using Mindfulness/ACT (see Image 6 below). The workshops were facilitated by senior members of the psychology team from a large UK NHS Mental Health Trust.

Figure 6. Research Design (taken from Cook et al., 2019: 4)

The original design suggested that after three of the five sessions there would spaces, facilitated by myself and the research assistant, for everyone to come together to reflect on the workshop and engage in critical discussion/evaluation.2x The first post workshop follow-up session of each course did not include the professionals because the project team considered it too soon for family carers to talk freely if they were present. These would function iteratively, building on knowledge gained from the previous one to shape the next. They were places where people could discuss their impressions of the course, evaluate the process and content and identify its impact. These communicative spaces were where knowledge about connections between concepts, theories and practices could be generated, knowledge that would inform future courses and wider practice. In practice, however, as family carers began to recognise these spaces as vital to their understanding of their own learning, they began to be incorporated into the workshop spaces. In due course, they became embedded as part of the course design.

-

Practicalities: Creating conditions for participation and mess

Mess with creative potential (Type 3 above) does not happen without a great deal of planning. The following gives some indication of the type of activities that create spaces for productive mess.

Recognising the issues: In FaBPos, as in most participatory projects, there were immediate issues to consider in setting up communicative spaces that bring together people with different perspectives and experiences, and different thoughts about what is important to consider. This space could not mimic the professional/practitioner ways of being as this was likely to distance those for whom this was alien. The challenge was to enable everyone involved, including the facilitators of the course and the researchers, to feel comfortable enough to be honest together about their reflections to get into a mess together and find their way out.

Our community of practice faced historical issues likely to create barriers to communication, learning and change. These included:

Some family carers who had experienced professional/practitioner expertise and found it lacking (and had no power to elicit service change) were angry. Voicing that anger was appropriate in a communicative space but their anger they might also mean they found it hard to listen, especially to the perspectives of professionals/practitioners.

Many family carers were angry with services but not necessarily the professionals/practitioners who were trying to provide those services who they generally liked (even though they thought them ineffective!). They were reluctant to express any critical ideas and risk offending people they liked or, as one family carer said, to ‘blot my copy book’.3x Colloquial term: if you blot your copybook you do something that offends social customs/negatively affects someone's opinion of you meaning they could be less well disposed to you in future. Whilst avoiding being involved with health services that they felt did not meet their needs (family support, respite, psychological services etc) they still needed health services for other reasons, so were reluctant to speak out.

Some family carers were tired of having to fight. They were so exhausted by their complex lives and trying to work with ineffective services that they had no reserves of energy to speak out again. Their experience was that speaking out had not made a difference before and so was a waste of their energies.

Professionals/practitioners (the course facilitators) wanted to improve their practice, to make it work better for families. They had considerable expertise, had studied for a long time, had vast experience of working with families and in general had a good rapport with them. They considered themselves to be family centred, taking their cue from families in relation to their practice. One had been working on the use of mindfulness for people with learning difficulties and their families for many years and had a wealth of experience to reflect upon and impart. The facilitators were influenced by current understandings of what was good and effective practice in their profession. In addition, their understanding of the research was predominantly that it would enable them to improve what they already did, not that the outcome would be radical changes in their thinking about the fundamental nature of their practice. The main learning would sit with the family carers, not them.

As an academic committed to developing research spaces for shared learning, my hope was that we might all, including myself as researcher, unearth new understandings that would have an impact on our practice. The aim was to unlearn and learn together using our diverse experiences and knowledge to create something that would make a meaningful difference for everyone involved, including the facilitators and in some way, to some extent and at some stage, we would all need to, as Winter (2002) suggested, enquire into and reflect upon our own practice and the impact of our engagement.

Building relationships: Informal pre-research conversations were used to furnish some of the most practical ways of creating the basis for supporting a propitious environment. They were carried out in people’s homes by the research assistant who then became integral to the workshops as a facilitator. When family carers arrived at the first workshop they would see at least one familiar (and friendly) face.

The environment: The research assistant sourced locations that would offer familiarity to family carers. It was important that the venue was not an NHS site and that the space was big enough for everyone to mix without divisions. It did not have to be a perfect space. In reality, when things did not quite work out as planned, this seemed to immediately bring people together to address them. Indeed, as family carers were often more familiar with the spaces than the facilitators, it was noticeable how often they took charge in such circumstances. This contributed to breaking the ice and building more equal relationships. Sharing tea/coffee and having time to tell tales about the experiences of the first journey to the venue, particularly if there was a little incident such as getting lost, taking the wrong metro (tube), not finding the building, something people could laugh about with each other and share the experience, seemed to establish the first phase of dialoguing (especially if the ‘lost’ experience was that of the facilitators or myself).

Positioning the notion of critique: In the UK, the term ‘critical’ can take on negative connotations it being considered disrespectful and likely to alienate the person being critical from those with alternative positions. The need to be critical within the research process was introduced to family carers during discussions at the start of each course. It was framed as a way of supporting future families (a motivation for participation revealed during the initial interviews). If family carers were not honest about how the course was working, and said it was going well for them when it was not, it would perpetuate the cycle of family carers coming to ineffectual courses. This encouraged those who may have been nervous of being critical, especially of those perceived as having expertise or power over them, to make their voices heard. Not all family carers were, however, shy about being critical.

-

Course one, workshop one: Mess in action

At the first workshop of Course One, after the introductions, the lead facilitator explained how the five workshops would be organised and the principles of Mindfulness and ACT. Near the end of the workshop one family carer expressed her frustration with this. She wanted to hear from the other family carers, hear about their lives and their stories, to tell her own story and share her knowledge. She could not be interested in what the facilitators were saying at this point; she had a different imperative. Other family carers agreed that they needed space to talk together and to find out more about each other. The facilitators stopped what they were doing and let the families talk. Family carers talked about their loved ones, about their pain, their despair over services and fears for the future of their relative. They talked about elements they had found to be supportive to date (usually things initiated by other family carers or family centres) and things that were ‘absolutely useless’ (mostly NHS services). This is how the first workshop ended.

In the post-workshop discussion session, facilitated by the research assistant and me, family carers continued conversations begun earlier, telling their stories and offering their experiences to each other. They were open and honest, keen to touch base with people who had a lived understanding of what they were going through. At some point I ventured to suggest that maybe they had not found the workshop very useful and that perhaps they would prefer a group where they could be together without professional involvement. The family carers had a different perspective, however. They thought the workshop had gone well. Discussions followed about why that might be, given that they had not really engaged with the central purpose of the workshop (Mindfulness/ACT). The reason they offered was that they had enjoyed speaking with each other, but they also looked forward to having this moderated in some form in later workshops. Several family carers said they had already been part of family groups but had stopped attending as they found they became places where the talk did not lead to anything helpful. Having forged a space to connect with each other they now felt more ready and able to begin Mindfulness/ACT at the next workshop. They valued the fact that in this first workshop they had been able to say to the facilitator that they needed to do something differently and that the facilitator had stepped back to provide that space. Their voices had been acted upon and this made it a good workshop, one they had enjoyed. Through their agency they had begun to take some responsibility and control and build the kind of relationships that would support critical enquiry through a communicative space.

Later in the week I met with a somewhat disappointed facilitator. He felt that because the family carers had not engaged with the theories of Mindfulness/ACT the workshop had not been successful. He was unsure where to go next if they did not want to engage. I was able to recount the rather more positive family carer perspective. After analysing what had been said (the data) in the post workshop follow-up session I had some insight into what worked for them, and why. Firstly, family carer data highlighted the imperative of giving time to building relationships (something they had inserted into the workshop by their actions rather than being planned for by the facilitator). Secondly, the facilitator had given the family carers the space to do what they needed; he had not kept them ‘to task’. In this way family carers had experienced agency by shaping the content of this workshop.

The actions of the family carers in the workshop had initially left the lead facilitator confused about what to do at the next workshop. He felt his professional knowledge had not been welcomed by the family carers and this left him unsure about how to go forward; he was in a mess. Hearing what had worked from the family carer perspective was a critical/pivotal moment for him. It led to a change in thinking, not about the content of the workshops, but about how that content was made accessible. For the next workshop he planned space at the beginning for family carers to talk together. As the family carers talked, he could hear what their issues, stresses and difficulties had been during the week. Listening to them, he could then choose an exercise that might help with thinking about that experience and its meaning. The agenda was thus set from what was uppermost in the minds of those who were living out the daily reality of coping with stress and complexity.

When in the research process people begin talking about getting into a mess, not really knowing what to do or what they are doing, this is an indicator that long-held beliefs are being tested, that spaces are opening up for new learning and actions to emerge.

The facilitators’ openness to uncertainty in the FaBPos project led facilitators to some key changes for the next workshop that would also prove to be important learning points for the facilitation of future workshops (Box 1).Box 1 Key changes made by facilitatorsLet go of control: enable shared agency within the space. Rather than planning discussions from a facilitator perspective, leave space for discussions to start from the issues that dominate the thoughts and lives of family carers. Do less planning but do plan more time for discursive dialogue. Having post-workshop follow-up sessions (communicative spaces) designed into the research process gave access to understanding what would support effective ways to engage together that would otherwise have been lost. The facilitators would have recognised that things had not gone as planned and redesigned the next workshop based on their own perception that it had not gone as they had hoped. There was the potential to produce an outline for the second workshop that again introduced Mindfulness/ACT without stepping back and first giving the family carers space to discuss their pressing issues. This could have adversely affected the building of trusting relationships.

-

Learning

At the start of the research, pre-course discussions with facilitators revealed that they understood the notion of participatory research as learning, but they saw this as predominantly family carer learning. They had not anticipated the potential for it to disrupt their own ways of acting. Now, as the workshops progressed, the positive outcome of experiencing being ‘in a mess’ themselves, and of learning to let go of their initial plans for the workshops, became evident. Family carers now talked freely and honestly, even using examples of their feelings, and using language to describe those feelings, that previously they might not have used in front of professionals. They engaged in Mindfulness/ACT and collaborative critique of their own behaviours. Seeing this, this facilitator now conceptualised his role very differently, not as the lead but as responsible for adding the ‘professional dye’.

The big thing from me is that I see my role getting smaller and theirs [family carers] getting bigger – I just add just a small amount at the right time – like dye in the water. I arrive with a big load of stuff to go through. I now have the confidence to be leaner – to let it go. Not to add where it’s not needed. (Facilitator 1: final feedback loop)

This is not, however, how these professionals were generally trained. They were trained to take responsibility for controlling the space and for imparting their knowledge to those in that space. It was hard at first to understand that the latter could be achieved by not being the leader but rather by being what this facilitator termed the ‘invisible facilitator’.

… when I run a group like this I will feel quite anxious and quite … I guess intimidated to start with…my default position, when I feel like that, is to over prepare, to have an agenda, to, you know, come with a PowerPoint that I've prepared in advance … something I'm really conscious of … is how I manage my own anxieties so I can be less in control, and let it be led by families, rather than myself … that is quite effortful, actually, to be seen as that invisible facilitator. (Facilitator 3: group 3 follow-up session)

In a later follow-up session, the lead facilitator told family carers how disappointed he had been about the first week, how he had thought it had not gone well at all. In the light of what happened after that, the changes that facilitators had made, and the value the family carers saw in working in this way, this seemed funny, and everyone laughed.

Family carers also learnt, for themselves, new ways of acting. Recognising how this learning was achieved was crucial for the future rollout of the project. Several elements seemed to be central in this:

Mess in relationally based communicative spaces: Communicative spaces were enabling people to reflect on their own behaviours, unpick their usual responses, habits and customs and to dive into new territory. The value of unpicking accepted knowings was that it provided conditions for shaping new knowings. Accepting ‘not knowing’ could however, leave people feeling in a mess: not knowing what to think or do next. This destabilising activity, instrumental in opening up space for creating new possibilities, was likely to be uncomfortable. The importance of time and space for building relationships was therefore crucial if people were to have the confidence to engage in self-reflection made public and critiqued in public. For people to be strong enough to let go of current imperatives and construct their own ways of changing personal behaviours, the communicative space needed to be a place of supported critique. This included support for the facilitators who, in the FaBPos project, had been supported by the family carers when amending their plans and usual ways of acting. When describing how she experienced the communicative spaces, this family carer neatly outlined how they needed to be:

… comfortable enough to have the serious conversation. And, kind of, being quite open and honest. Kind of, about the difficulties and challenges in our lives. But, on the flip side, kind of … We’re also able to chip in with funny bits of stories and … Obviously tag onto other people … Whatever other people are saying. Just to have … You know, that bit of humour and that bit of fun as well. (Family Carer, group 1: feedback session)

Sharing control: throughout the project most family carers alluded to their lack of agency as something they experienced in their daily lives, especially in their encounters with service providers. One family carer put this very clearly when she said she was fed up of ‘all this give and take’. This is generally a phrase used to praise reciprocal behaviour. ‘Give and take’ is seen as good. As she pointed out, however, professionals always wanted to give her something and she was supposed to take even if it was not something she needed. On the other hand, she had a lot to give and she wanted what she could give to be used. A key learning from the project therefore, one that was likely to have wider impact across services, was the recognition by the facilitators of the need to take this into account. Instead of conceptualising facilitation as the act of being in control, the lead facilitator recognised himself as a more nuanced practitioner, one who waited for spaces to contribute rather than planning his contribution unilaterally.

… it’s so easy for us as professionals to think these are the latest psychological benefits, we should make them available. Which is…a decent start. But how you go about making them available is you ‘do unto them’. I think one of the things that we’ve learnt in this course is you don’t ‘do unto them’. That’s so crucial. So, dismantle the doing unto … the giving, and do more taking. (Facilitator 1: final feedback session)

Facilitators became engaged in, rather than controlling of, the collaborative, critical reflexive processes. Their learning provided meaningful spaces for family carers to learn for themselves, improving not only their lives, but the lives of those around them, including the person they cared for.

Embracing the unexpected: Learning to ‘dismantle the doing unto’, to ‘take’ and ‘give’ as invisible facilitators was not a potential impact identified at the project proposal stage for this research. Identified impacts had been family-carer oriented. It was, however, a vital piece of learning that enabled family carers to understand and find their own way to changing certain unhelpful behaviours, to incorporate Mindfulness/ACT in a meaningful way in their own lives. A key purpose of doing research in this participatory, dialogical way was to reach beyond original understandings of issues to reveal something that might not have been known before. These are unexpected knowledge and impacts that may have been lost to more traditional, linear research processes. In the FaBPoS project the collective self-reflective enquiry of PR facilitated change in constructs for action of both professionals and family carers, changes that had not been expected at the outset. As this facilitator noted:

… one of the big breakthroughs with this is just the way, together, we’ve created something. What's been great is doing it together because what we've ended up with is different from what we started off with … we have created something that none of us would have thought of if we had not gone through it … (Facilitator 1: final feedback session)

Accepting an emerging research design: Family carers had been involved in the original research design, but the actions of those involved in the research itself revealed the need for further changes. Embedding the reflection time (originally envisaged as occurring after the workshops) into the body of the workshops created conditions for change to happen as part of the practice of those workshops. This blurred the boundaries between research and practice. Change did not happen at the end, it happened throughout. A hallmark of a genuine participatory action research process is that, as Wadsworth (1998: 5) stated, it may

… change shape and focus over time (and sometimes quite unexpectedly) as participants focus and refocus their understandings about what is ‘really’ happening and what is really important to them.

-

Reflections: Can participation and mess take their place?

PR redefines the relational environments within research and the quality criteria for that research. Committed to socially just change it can have a powerful impact on the way people, drawn from diverse life-worlds, think and act. This relationally based, democratic, dialogic form of enquiry draws on many knowledges, not just the prevailing or dominant, through the processes within research. Its focus on critical reflexive practice holds the potential to go beyond researching the ‘knowns’ to surfacing essential ‘unknowns’ (or tacitly known ‘knowns’) meaning it is likely to have impacts that that might be unexpected and personally, or systemically, challenging. The act of forging new ideas, of learning together, of not being afraid of not knowing, can destabilise personal and professional knowing, create messiness and uncertainty, yet it is this drawing on the multiple positionings and synthesising shared knowledge becomes the starting point for taking action and rebuilding practice. PR does not seek to maintain stability, to keep within certainty. Through investing in different knowledge, specifically experiential knowledge and the knowledge of the seldom heard, it shakes the pillars of certainty.

The role played by uncertainty is one that differentiates PR processes from more experimental models for research. It is neither better nor worse, but different, with different processes, expectations and impacts. The challenge then is for those who commission research to cut loose from the apron strings of distance and certainty and recognise the value of alternative forms of enquiry for effecting social change. The delivery model of research, where researchers do the research from an external perspective and then report back, continues, however, to be perpetuated despite co-produced research being seen as ‘a key concept in the development of public services. It has the potential to make an important contribution to all of the big challenges that face social care services’ (SCIE, 2015). Whilst in the UK the value of PR is discussed in health and social care research, it remains slow to effect change in commissioning approaches. They continue to straitjacket PR into frameworks suited to more experimental, predetermined methodologies that fail to give space to the true processes of a relational-based, emergent research approach.

This article challenges research commissioners, especially those commissioning research aimed at addressing epistemic injustice, to consider what kind of knowledge is required from research, how it might be generated and who needs to learn by that process. As McKee (2019: 557) states, far too often there is a gap between research and policy and practice with too much research being undertaken that has little relevance to real-life problems. I would add that far too little research seeks to truly destabilise the status quo in ways that make space for change to happen. Policymaking continues to be defined by outcomes from forms of research that fail to make a difference. Learning for social change is much more demanding than being given information; it is a process born out of active engagement and socially constructed understandings. All too often those who ‘need to learn’ are not involved in the challenge of confronting epistemological, systemic or professional knowing creating barriers to change. The deeply critical form of participation exemplified by PR is not an easy place to be; it is not an easy science. It can, however, be an exciting place to be with the rewards intrinsic to the process, having immediate impacts on the lives and working practices of those involved but the learning can go on to ripple out into other social ecosystems. So, let’s, like David above, try and let our minds slip a little, get ourselves in a mess, and learn something we did not know.

-

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the work of all the family carers, facilitators and research assistants who have contributed to this project. Their time, energy, clear insights and deep commitment have been truly inspiring. For all those engaged in the research, it was our sincere hope and intention that this work will go on to make a difference to how those with lived experience are engaged in researching and developing service provision that affects their lives.

This paper draws on independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Research for Patient Benefit (RfPB) Programme (Grant Reference Number PB-PG-1014-35062). The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

References Cook, T. (2006). Collaborative action research for development and evaluation: A good fit or the road to myopia? Evaluation, 12(4), 418-436.

Cook, T. (2009). The purpose of mess in action research: Building rigour through a messy turn. Educational Action Research, 17(2), 277-292.

Cook, T. (2012). Where participatory approaches meet pragmatism in funded (health) research: The challenge of finding meaningful spaces. Forum: Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(1), Art. 18. https://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-13.1.1783

Cook, T., & Inglis, P. (2008). Understanding research, consent and ethics: A participatory research methodology in a medium secure unit for men with a learning disability. http://northumbria.openrepository.com/northumbria/browse?type¼author&order¼ASC&value¼Cook%2C+Tina

Cook, T., Noone, S., & Thomson, M. (2019). Mindfulness-based practices with family carers of adults with learning disability and behaviour that challenges in the UK: Participatory health research. Health Expectations, 22, 802-812. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12914

Edelman, M. (1964). The symbolic use of politics. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Eraut, M. (2000). Non-formal learning and tacit knowledge in professional work. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 70, 113-136.

Filipe, A., Renedo, A., & Marston, C. (2017). The co-production of what? Knowledge, values, and social relations in health care. PLoS Biology, 15(5), e2001403. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2001403

Griffiths, G.M., & Hastings, R.P. (2014). ‘He’s hard work but he’s worth it’. The experience of caregivers of individuals with intellectual disabilities and challenging behaviour: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 27(5), 401-419.

Habermas, J. (2003). Truth and justification. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Heaney, S. (1999). Poetry: How it has fared and functioned in the twentieth century. Sounding the Century, BBC Radio 3, 17 January.

International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research (ICPHR). (2013). Position Paper 1: What is Participatory Health Research? Version: Mai 2013. Berlin: International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research. Lead Editor: Michael Wright. www.icphr.org

International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research (ICPHR). (2020). Position Paper 3: Impact in Participatory Health Research. Version: March 2020. Berlin: International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research. Lead Editor: Tina Cook. www.icphr.org

Kemmis, S. (2001). Exploring the relevance of critical theory for action research: Emancipatory action research in the footsteps of Jürgen Habermas. In P. Reason & H. Bradbury (Eds.), Handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice (pp. 91-102). London: Sage.

Kemmis, S., & McTaggart, R. (1990). The action research planner. Geelong: Deakin University Press.

Lenette, C., Stavropoulou, N., Nunn, C., Kong, S.T., Cook, T., Coddington, K., & Banks, S. (2019). Brushed under the carpet: Examining the complexities of participatory research. Research for All, 3(2), 161-179. https://doi.org/10.18546/RFA.03.2.04

McKee, M. (2019). Bridging the gap between research and policy and practice comment on “CIHR health system impact fellows: Reflections on ‘driving change’ within the health system”. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 8(9), 557-559. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2019.46

McTaggart, R. (1997). Guiding principles for participatory action research. In R. McTaggart (Ed.), Participatory action research: International contexts and consequences (pp. 25-43). New York: Albany.

Mellor, N. (2001). Messy method: the unfolding story. Educational Action Research, 9(3), 465-484, DOI:10.1080/09650790100200166

Reason, P. (1998). Political, epistemological, ecological and spiritual dimensions of participation. Studies in Cultures, Organisations and Societies, 4, 147-167.

SCIE. (2015). Co-production in social care: What it is and how to do it. Guide 51. https://www.scie.org.uk/publications/guides/guide51/

Wadsworth, Y. (1998). What is participatory action research? Action Research International, Paper 2. http://www.scu.edu.au/schools/gcm/ar/ari/p-ywadsworth98.html

Wenger, E. (no date). Communities of practice and social learning systems: The career of a concept. https://wenger-trayner.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/09-10-27-CoPs-and-systems-v2.01.pdf

Winter, R. (2002). Managers, spectators and citizens: Where does “theory” come from in action research? In C. Day, J. Elliott, B. Somekh, & R. Winter (Eds.), Theory and practice in action research: Some international perspectives (pp. 27-44). Oxford: Symposium Books.

Yang, L., Chang, K., & Chung, K. (2012). Methodologically rigorous clinical research. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 129(6), 979e-988e. DOI:10.1097/PRS.0b013e31824eccb7

-

1 Colloquial term meaning no longer being able to be objective as those involved are too close to each other.

-

2 The first post workshop follow-up session of each course did not include the professionals because the project team considered it too soon for family carers to talk freely if they were present.

-

3 Colloquial term: if you blot your copybook you do something that offends social customs/negatively affects someone's opinion of you meaning they could be less well disposed to you in future.

Citeerwijze van dit artikel:

Tina Cook, ‘Participatory Research: Its Meaning and Messiness’, 2021, januari-maart, DOI: 10.5553/BO/221335502021000003001

Beleidsonderzoek Online |

|

| Artikel | Participatory Research: Its Meaning and Messiness |

| Auteurs | Tina Cook |

| DOI | 10.5553/BO/221335502021000003001 |

|

Toon PDF Toon volledige grootte Samenvatting Auteursinformatie Statistiek Citeerwijze |

| Dit artikel is keer geraadpleegd. |

| Dit artikel is 0 keer gedownload. |

Tina Cook, 'Participatory Research: Its Meaning and Messiness', Beleidsonderzoek Online februari 2021, DOI: 10.5553/BO/221335502021000003001

|

Participatory research is increasingly being perceived as a democratic and transformative approach to social situations by both academics and policymakers. The article reflects on what it means to do participatory research, what it contributes to broader knowledge building, and why mess may not only need to be present in participatory research but encouraged. The purposes of participation and mess as nourishment for critical enquiry and more radical learning opportunities are considered and illuminated using case study material from the Family Based Positive Support Project. Vooraf Participatief actieonderzoek en responsieve evaluatie staan volop in de belangstelling bij beleidsmakers en onderzoekers. Dit type beleidsonderzoek en -evaluatie beoogt democratisch, inclusief én impactvol te zijn. Het gaat om onderzoek mét in plaats van óver mensen. En het is actiegericht: onderzoek wil bijdragen aan concrete oplossingen door met betrokkenen gezamenlijke (verbeter)acties te ontwikkelen in de praktijk, en daarop te reflecteren en van te leren. Dit alles met het oog op sociale inclusie. Het zijn mooie idealen, maar wat betekent dit in de alledaagse, vaak weerbarstige onderzoekspraktijk? Op 20 januari 2020 organiseerde prof. Abma daarover een symposium, getiteld ‘Responsive, Participatory Research: Past, Present and Future Perspectives’ (Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam). De rode draad op het symposium was de vraag wat goed en ethisch verantwoord participatief onderzoek is, en wat dit vraagt van onderzoekers en beleidsmakers. Drie lezingen op deze conferentie zijn nadien omgewerkt tot essays om lezers van Beleidsonderzoek Online vanuit verschillende perspectieven beter kennis te laten maken met deze vorm van onderzoek: Prof. Weerman en haar team focussen in hun bijdrage op het zich in de praktijk ontwikkelende onderzoeksdesign en het inzetten van creatieve methoden om participatie te bevorderen. Ze gaan na welke kwaliteitscriteria aan participatief actieonderzoek worden gesteld en hechten daarbij met name aan eisen ten aanzien van participatie, samen leren en verschil maken (zie BoO juli 2021). Ze benadrukken het belang van creativiteit en flexibiliteit. Prof. Abma bespreekt in haar artikel de normatieve dimensies en de ethiek van participatief actieonderzoek (zie BoO september 2020). Ze illustreert met een voorbeeld uit de crisishulpverlening aan GGZ-cliënten dat participatief actieonderzoek niet slechts een methodisch-technische exercitie is, maar een sociaal-politiek proces waarbij bestaande machtsverhoudingen verschuiven om ruimte te geven aan nieuwe stemmen en kennis. Dit omvat het zien van en stilstaan bij ethisch saillante dilemma’s en morele reflectie. De bijdrage van prof. Cook (zie BoO februari 2021) gaat over de weerbarstige praktijk van participatief actieonderzoek. Het doel is samen leren en voorbij geijkte oplossingen komen. Zij laat zien dat dit uitdagend is voor professionals die geconfronteerd worden met burgers die feedback geven en vragen om het (deels) loslaten van vaststaande professionele kaders. Er ontstaat dan ongemak en onzekerheid, maar zo beoogt en laat Cook overtuigend zien, deze ‘mess’ (niet meer goed weten wat goed en nodig is) is productief om te komen tot hernieuwde inzichten en innovaties. (Introductietekst opgesteld door prof. T. Abma) |

Dit artikel wordt geciteerd in

- Introduction

- Background

- What does it mean to do participatory research?

- The purpose of mess

- Challenges from (and to) the field

- The FaBPos Project

- Practicalities: Creating conditions for participation and mess

- Course one, workshop one: Mess in action

- Learning

- Reflections: Can participation and mess take their place?

- Acknowledgements

- References

- ↑ Naar boven